Is cutting marble difficult?

No, marble is relatively easy to cut compared to harder stones like granite, but achieving precise, clean cuts requires understanding its physical properties and selecting the appropriate cutting techniques, tools, and safety measures.

Marble’s reputation for being difficult to cut stems largely from its tendency to chip or crack if handled incorrectly. However, its inherent softness, a key characteristic, actually makes it more workable than many other natural stones. The real challenge lies not in brute force cutting, but in mastering the correct approach tailored to marble’s specific nature and the project’s requirements. Successfully cutting marble hinges on respecting its physical limitations and employing the right methodology.

I. The Physical Properties of Marble: Understanding the Material

Marble is a metamorphic rock primarily composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite (calcium carbonate – CaCO₃) or dolomite (calcium magnesium carbonate – CaMg(CO₃)₂). This composition is fundamental to its workability. On the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, marble typically falls between 3 and 4. To put this in perspective, granite, a common alternative countertop stone, ranges from 6 to 7, and diamond, the hardest natural substance, sits at 10. This relative softness means standard steel tools can scratch marble, and specialized diamond tools can cut through it efficiently. However, this softness is a double-edged sword. While it makes initial cutting easier, marble is also more susceptible to scratching, chipping, and cracking during the cutting, handling, and finishing processes compared to harder stones. Its crystalline structure, formed under heat and pressure, can also contain natural fissures or veins that may act as weak points prone to splitting if stressed incorrectly during cutting. Furthermore, the carbonate minerals react with acids (even mild ones like vinegar or lemon juice), making chemical etching a concern during fabrication and use, though this doesn’t directly impact the mechanical cutting process itself. Understanding this combination of softness and brittleness is crucial for selecting the right cutting approach.

II. Cutting Techniques: Matching Method to Need

Marble fabrication primarily utilizes two distinct cutting methodologies, each suited to different scales and precision requirements: continuous cutting and discrete cutting.

- Continuous Cutting (Sawing): This is the dominant method for bulk processing and straight cuts in industrial settings and professional workshops. It involves feeding the marble slab or block steadily against a rotating diamond blade (mounted on a bridge saw, gang saw, or block cutter). The blade cuts in a continuous line. This method is characterized by high speed and efficiency, making it ideal for dimensioning slabs, cutting tiles to standard sizes, or making long straight cuts for countertops. However, it demands significant investment in specialized, heavy-duty machinery (like hydraulic bridge saws or wire saws) and requires skilled operators to ensure accuracy, blade longevity, and safety. While excellent for straight lines, intricate curves or complex shapes are generally not feasible with standard continuous sawing setups.

- Discrete Cutting (Shaping & Detailing): This category encompasses techniques used for more intricate work, smaller jobs, or on-site adjustments. It includes:

- Hand Cutting with Saws: Using smaller power tools like angle grinders fitted with diamond blades or specialized hand-held stone cutters (“stone routers” or profiling tools). This offers maximum flexibility for cutting curves, sink openings, notches, or making adjustments during installation.

- Waterjet Cutting: An advanced discrete method that uses an extremely high-pressure stream of water mixed with abrasive garnet particles to erode the stone. This is exceptionally precise (capable of intricate details and sharp corners with virtually no chipping) and generates no heat, eliminating thermal stress cracks. It’s ideal for complex shapes, detailed inlays, or very delicate pieces. However, it’s slower than sawing for simple cuts and has higher operating costs.

- CNC Routing: Computer-controlled machines using diamond tool bits to mill shapes, edges, and holes with high precision and repeatability. Excellent for complex countertop profiles, sink cutouts, engravings, and batch production of intricate pieces.

Discrete cutting generally offers greater precision and flexibility for non-linear work compared to continuous sawing but is significantly slower for large-scale, straight cutting tasks. Waterjet and CNC represent the pinnacle of precision in discrete cutting.

III. Cutting Equipment: Choosing the Right Tool for the Job

The choice of equipment is intrinsically linked to the chosen technique and the scale/precision of the project:

- Industrial/Professional Equipment:

- Bridge Saws: The workhorses of stone shops. A diamond blade mounted on a moving beam (“bridge”) traverses over a stationary marble slab on a sturdy table. Hydraulic systems control the blade descent and slab movement. Essential for straight cuts on countertops and slabs. Water cooling is standard to control dust and blade temperature. Precision can reach ±0.5mm with high-end models.

- Gang Saws: Used primarily in quarries and large mills to slice massive marble blocks into multiple slabs simultaneously using multiple parallel blades. Not suitable for detail work.

- Wire Saws: Employ a diamond-impregnated steel cable running in a loop. Used for quarrying large blocks or cutting very thick stone where conventional saws cannot reach. Less common in fabrication shops.

- CNC Stone Centers: Combine a bridge saw structure with a rotating spindle that can hold various diamond router bits, drills, and polishing tools. Perform sawing, milling, shaping, edging, and drilling operations automatically based on digital designs. Represents the highest level of automation and capability in stone fabrication.

- Waterjet Cutters: Use ultra-high-pressure pumps (50,000-90,000 PSI) to propel water and abrasive through a nozzle, eroding the stone. Require specialized programming and handling of the abrasive slurry.

- Small-Scale/DIY Equipment:

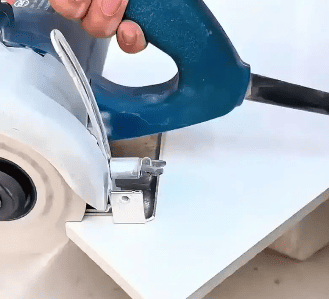

- Angle Grinders: Versatile and portable. When fitted with a diamond blade (specifically designed for dry or wet cutting marble), they can make straight cuts, curves, and openings. Crucially, they require extreme care, a steady hand, and robust safety gear (respirator, goggles, gloves, hearing protection) due to significant dust and kickback risk. Best for small cuts or adjustments.

- Circular Saws: Similar to angle grinders but designed for straighter lines. Can be used with diamond blades and guide rails for more controlled straight cuts on smaller pieces. Dust control is a major challenge.

- Jig Saws: Can be used with diamond-grit blades for cutting curves or internal openings in thinner marble tiles or small pieces. Slow and prone to chipping/blade breakage if not handled carefully. Not suitable for thick countertops.

- Wet Tile Saws: Bench-top or stand-mounted saws with a small diamond blade and a water reservoir for cooling/dust suppression. Primarily designed for ceramic and porcelain tiles, they can cut thinner marble tiles (e.g., 1/2″ or 3/4″) but are generally underpowered and lack the stability for thicker marble slabs or countertops (2cm/3cm). Using them for countertops is risky and often leads to poor results or damage.

The critical rule: Standard ceramic tile cutting tools are inadequate for marble slabs and countertops. Cutting thicker marble demands diamond blades specifically designed for stone cutting, mounted on sufficiently powerful and stable equipment, preferably with water cooling for dust control and blade life. For countertops, professional-grade bridge saws or waterjets are the standard. DIY attempts with inadequate tools are highly likely to result in chipping, cracking, blade damage, or safety hazards.

IV. Cutting Purpose: Defining the Difficulty Level

The perceived difficulty of cutting marble varies dramatically depending on the project’s goals:

- Bulk Processing & Rough Dimensioning (Lower Difficulty – with the right tools): In a quarry or large fabrication shop equipped with industrial gang saws, wire saws, or large bridge saws, cutting marble blocks into slabs or large panels is a core, routine process. While requiring significant machinery and expertise, the act of making large straight cuts through marble is fundamentally efficient and well-understood industrially. The difficulty is managed through scale, specialization, and powerful equipment. Chipping on the rough edges is acceptable as these will be trimmed later.

- Standard Countertop Fabrication (Moderate Difficulty): Cutting sink openings, appliance cutouts, and shaping the edges of marble countertops requires precision to avoid costly mistakes. Using bridge saws for straight cuts and CNC routers or waterjets for sink cutouts and edge profiling is standard. The challenge lies in achieving clean, chip-free cuts (especially inside corners and curves), managing the weight of large slabs, ensuring accurate templating, and executing complex edge profiles consistently. Experience and proper equipment are essential. Dry cutting smaller pieces or making adjustments on-site with angle grinders adds another layer of skill requirement to avoid damage.

- Artistic Carving & Intricate Detailing (High Difficulty): Creating complex sculptures, highly detailed architectural elements, or intricate mosaic pieces from marble demands the highest level of skill. This involves extensive use of discrete cutting and shaping techniques – diamond hand tools, grinders, routers, pneumatic hammers, chisels, and often waterjets or CNC for initial roughing out. The artist or fabricator must possess an intimate understanding of the stone’s grain, potential weak points, and how to remove material without causing fractures. Precision, patience, and artistic vision are paramount. This represents the pinnacle of difficulty in marble working.

- DIY & Small Home Projects (Variable Difficulty – Often High Risk): Cutting marble tiles for a backsplash with a wet saw is generally manageable with care. However, attempting to cut a thick marble countertop slab using DIY tools like an angle grinder or an undersized wet saw is fraught with difficulty and risk. Achieving straight, chip-free edges, cutting sink openings without cracking the slab, and managing the sheer weight and brittleness of the material are major challenges without professional equipment and experience. The likelihood of damaging the expensive stone or causing injury is significantly higher for DIYers tackling complex marble projects.

Conclusion: Balancing Ease with Precision

Cutting marble is fundamentally less difficult than cutting harder stones like granite or quartzite due to its lower Mohs hardness. Its relative softness allows diamond tools to cut through it efficiently. However, this ease of initial cutting is counterbalanced by marble’s susceptibility to chipping, scratching, and cracking. Therefore, the perceived difficulty shifts dramatically based on the context.

- Industrial Scale: Cutting is efficient and routine with specialized heavy machinery, minimizing the difficulty per unit cut.

- Precision Fabrication (Countertops): Requires significant skill, experience, and professional-grade equipment (bridge saws, CNCs, waterjets) to achieve clean, accurate, and chip-free results consistently. Mistakes are costly.

- Artistic Work: Demands the highest level of craftsmanship and specialized tools, representing significant difficulty in execution.

- DIY Projects: While thin tiles can be manageable, cutting thick slabs or complex shapes without professional tools is highly challenging and risky, often leading to poor results or damage.

The key takeaway is that while marble’s inherent properties make it cuttable, achieving high-quality, precise, and undamaged cuts – especially for demanding applications like countertops or art – necessitates the right combination of technique, specialized diamond-tool-equipped machinery, operator skill, and rigorous safety practices. Neglecting any of these factors quickly turns what should be a manageable process into a difficult and potentially disastrous one. For non-professionals, especially when dealing with valuable countertop slabs, engaging a qualified fabricator with the proper tools and expertise is almost always the safest and most reliable approach.